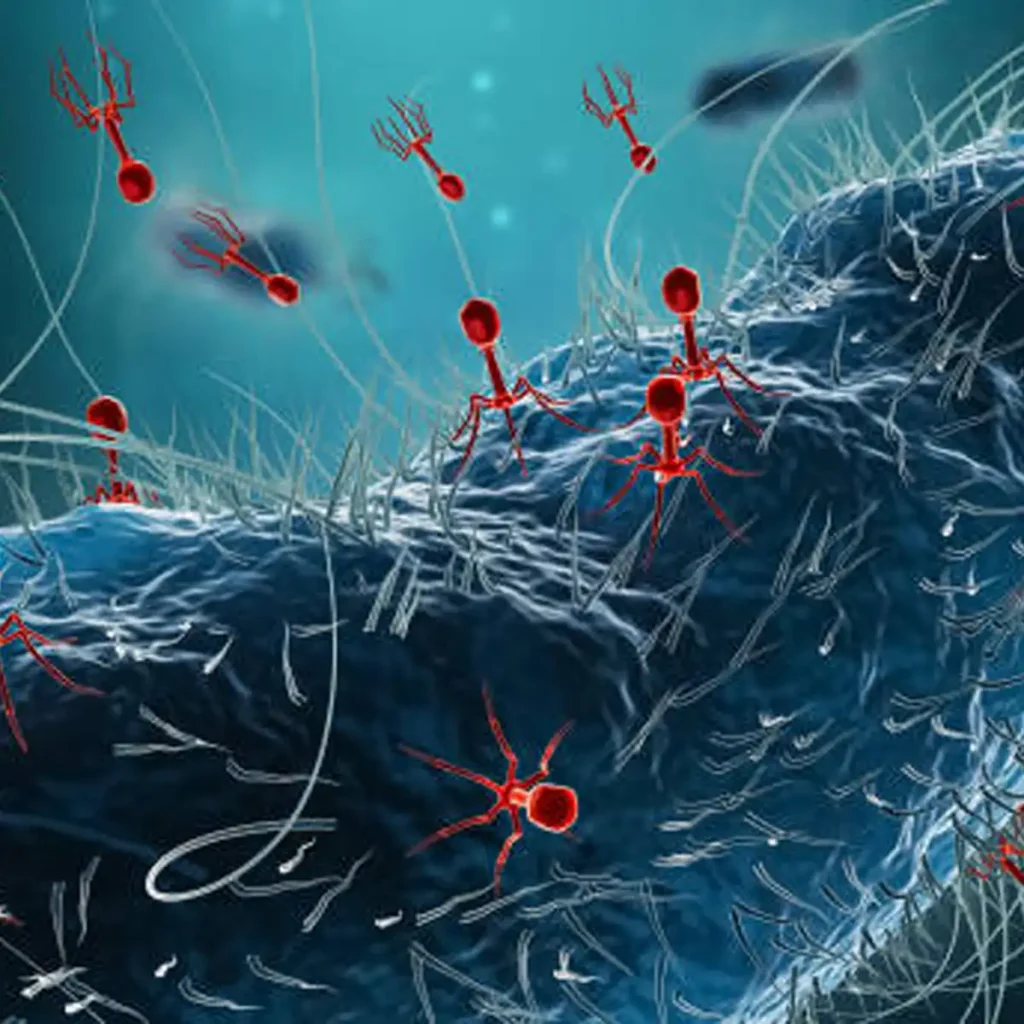

Antimicrobial resistance is accelerating across health systems and undermining routine care. Surgical prophylaxis, oncology regimens and neonatal medicine all depend on reliable antibiotics, yet resistant pathogens are eroding that foundation. In 2025, health services are searching for modalities that complement or bypass failing drugs. Bacteriophage therapy sits near the top of that shortlist because it targets bacteria with biological precision rather than broad biochemical force. Phages are viruses that infect bacteria. Lytic phages take over the bacterial replication machinery and burst the host cell, releasing progeny that propagate to matching targets. This self-limiting cycle creates a treatment that expands in the presence of a pathogen and contracts when the target is cleared.

The precision that once looked like a drawback now reads as an advantage. Many phages are specific at the species or strain level, so they leave commensal flora largely intact. That matters for patients whose gastrointestinal or respiratory microbiota are fragile after multiple antibiotic courses. It also fits the direction of personalised medicine in infectious disease, where therapy is matched to the organism rather than chosen as a broad cover.

Chronic and device-associated infections expose another property that sets phages apart. Biofilms protect bacteria against antibiotics and immune responses by encasing cells in a polymeric matrix. Several phages express depolymerising enzymes that degrade biofilm components. This makes them attractive for infections around prosthetic joints, fixation plates, vascular grafts and persistent sinus disease, where eradication depends on breaking the matrix as well as killing the bacteria.

The dosing logic is unusual for a medicine. In principle, phages continue replicating while the target persists, then decline as bacterial load falls. Clinical teams still set schedules and routes of administration, but the biology delivers a feedback loop that small molecules cannot match. In practice, this feature is constrained by immunity, local microenvironments and the need to reach the pathogen in sufficient numbers.

Real fact: Lytic bacteriophages replicate only in the presence of their specific bacterial hosts, which means therapeutic activity tends to self-limit as pathogen burden declines.

Regulatory status in the UK and EU

Phages are living agents that evolve, which places them awkwardly within frameworks designed for fixed chemical entities and standardised biologics. The dominant regulatory conversation in the UK and EU treats them as medicinal products that must meet quality, safety and efficacy standards while acknowledging their biological complexity. Authorities have used existing routes to enable access for individual patients under professional oversight. At the same time, longer-term work continues how to evaluate and authorise products that may require periodic adaptation.

In the UK, MHRA pathways most often used for phage therapy are exceptional and compassionate use, with case-by-case governance and documentation. In Europe, national regulators apply analogous mechanisms, and pan-European dialogue continues through competent authority networks. The central challenge is to preserve patient safety and product integrity without freezing a therapy that may need to change composition as bacterial populations shift.

Classification influences everything that follows. When phages are treated as part of the advanced therapy medicinal products family, expectations for manufacturing and control rise to the level applied to other complex biologicals. That means explicit genetic characterisation, validated purification processes, and environmental and adventitious agent controls that satisfy GMP manufacturing standards. The requirements are achievable, but the cost and time are significant for small producers or hospital-linked centres that currently supply many clinical cases.

Dose definition is another sticking point. Phage preparations are quantified by plaque-forming units, which measure active viruses capable of infecting the host strain. Ensuring that potency is consistent across batches is technically demanding, particularly when a cocktail contains multiple phages with different growth characteristics. This makes stability, release testing and expiry dating more complex than for conventional antibiotics.

Finally, traditional drug approvals lean heavily on large randomised, controlled trials. That design becomes difficult when each course may require a tailored match between a patient’s isolate and a specific phage. Regulators recognise this constraint and are open to innovative designs. However, sponsors still need robust evidence that links the right phage to the right pathogen and shows clinically meaningful outcomes with acceptable safety.

Where clinical use is advancing

The strongest demand comes from infections where bacteria are protected by biofilms, located behind barriers, or inherently resistant to multiple antibiotic classes. In these contexts, clinicians need targeted activity and local delivery options.

In chronic respiratory disease, patients with cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis can harbour persistent Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Burkholderia species that resist multiple regimens. Nebulised phage therapy appeals because it can be directed to the airways and combined with airway clearance and adjunct antibiotics. Individual cases and small series suggest that carefully matched phages can reduce pathogen load and improve symptoms, especially when standard care has been exhausted.

Orthopaedic infections around prosthetic joints or plates illustrate the interplay between biofilms and hardware. Revision surgery, washouts and long antibiotic courses are common, yet recurrences occur if biofilms persist on metal or cement. Phages that degrade biofilm components can be applied locally during surgical procedures or through drains and sinus tracts to reduce bacterial resilience and restore antibiotic susceptibility.

In haematology and oncology, patients undergoing chemotherapy, stem cell transplantation, or CAR T therapy may become vulnerable to multidrug-resistant pathogens. Care teams sometimes request phage therapy as a salvage option when conventional antibiotics fail. These cases require meticulous microbiology, interdisciplinary governance and clear monitoring plans, because patients are immunocompromised and procedural risks are higher.

Across these settings, real-world evidence is growing through compassionate use reports, observational cohorts and prospective service evaluations. The trend is consistent. When a phage or cocktail is well matched to a documented pathogen, delivered through an appropriate route, and supported by surgical or procedural measures when needed, clinical benefit is plausible and sometimes striking. The inverse is also true. Mismatched or poorly delivered phages rarely help.

Ex vivo and in vivo strategies

Two therapeutic strategies dominate. Ex vivo approaches build on precision microbiology and tailored compounding. The care pathway begins with a robust culture and susceptibility profile. A specialist laboratory screens the patient’s isolate against a library to identify active phages. The laboratory then prepares a product that meets sterility and purity requirements and ships it for clinical use. Routes include topical application to wounds, sinus irrigation, nebulisation into the lungs, intravesical instillation into the bladder, or direct application during orthopaedic procedures.

In vivo strategies aim to deliver phages or non-viral vectors that carry phage-derived enzymes to the infection site without prior ex vivo matching. The idea is attractive for urgent infections, but it raises questions about distribution, persistence and immune responses. Lipid nanoparticles, polymeric carriers, and engineered phages are under evaluation to improve delivery to difficult sites such as bone, biofilm-laden hardware, and poorly perfused tissues. Meanwhile, combined strategies that pair local application with systemic antibiotics are common, reflecting the need to control both planktonic and biofilm-embedded bacteria.

The NHS pharmacist’s role in compassionate use

Within the NHS, the specialist pharmacist is central to safe access. This is a new type of workload that blends procurement, aseptic preparation, governance and patient safety.

Sourcing and authentication begin the process. Pharmacists verify supplier credentials, quality documentation and test results. Where hospital-linked or academic labs provide phages, the pharmacy team ensures that agreements cover liability, chain of custody and release criteria. If commercial suppliers are involved, staff confirm that the product specification matches the organism and route of administration planned by the clinical team.

Preparation and labelling call for aseptic technique and meticulous documentation. Many courses require bespoke dilution and unit dose preparation shortly before administration, with cold chain controls and time-sensitive expiry. Labels must reflect PFU content, route, storage and handling instructions, as well as standard patient identifiers. Because the product is a living agent, pharmacy procedures also consider environmental controls and waste handling.

Risk management spans clinical and regulatory dimensions. Pharmacists coordinate with infectious diseases, microbiology and surgical teams to monitor for infusion reactions, fever and local inflammatory responses. They also document adverse events and liaise with governance teams on MHRA reporting where applicable. For nebulised or intranasal routes, respiratory physiologists may be involved to optimise delivery. Throughout, pharmacists maintain the audit trail needed for case reviews and for any future submission that draws on institutional experience.

Standardisation and the product pathway

If phages are to transition from bespoke cases to routine NHS practice, standardisation is unavoidable. Two models are competing for feasibility and impact.

The phage cocktail model mirrors the traditional pharmaceutical playbook. Sponsors develop fixed combinations that target high-priority AMR pathogens such as MRSA, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The advantage is clear labelling, scaled manufacturing, straightforward distribution and simpler reimbursement. The limitations are biological. Bacterial populations evolve, and strain coverage can drift. Cocktails need periodic updates, and regulators must agree on how to treat composition changes.

The personalised model treats phage therapy as a platform service. A patient’s isolate is sequenced and tested against a library. A matched phage or custom cocktail is then produced for that case under tight timelines. Clinical precision improves, and the risk of mismatch falls. The operational burden is heavy. Sourcing, manufacturing, release testing and shipping must happen quickly, or the patient deteriorates before treatment starts. Cost and infrastructure requirements are significant.

Either path requires GMP-ready facilities, validated analytics and scale-appropriate quality systems. Endotoxin control, sterility assurance, host cell protein removal, and phage identity testing are non-negotiable. Downstream processing methods such as filtration and chromatography are being adapted for phage size and stability. Without this manufacturing backbone, access will remain restricted to a limited number of compassionate cases.

Evidence standards and study design

High-quality trials are difficult but feasible if sponsors and regulators agree on designs that reflect the biology. When therapy hinges on matching a phage to an isolate, adaptive or umbrella designs can group patients by pathogen and site of infection, with shared comparators that reflect standard care. Endpoints should measure outcomes that matter to patients and services, such as infection resolution, time to source control, device retention and readmission rates, rather than only microbiological clearance.

Safety monitoring needs special attention. Phages are generally well tolerated, but immune responses, pyrogenic reactions from impurities and local inflammation can occur. This makes manufacturing quality, route selection and premedication protocols important. Pharmacovigilance systems should capture both acute events and any delayed effects, with transparent reporting to build confidence.

Clinical governance and ethics

Phage therapy is firmly within somatic treatment. Germline editing controversies are unrelated, but ethical questions still arise. When therapies are delivered under urgent conditions and evidence is evolving, consent documents must clearly outline knowns and unknowns, including uncertainties about long-term outcomes. Equity must be considered. If access depends on being near a hospital that has the right lab connections and pharmacists trained for this work, inequalities could widen. National networks that share libraries, protocols and quality documentation can mitigate geographic variation.

Data stewardship also matters. Case series and service evaluations are rich sources of learning if they use consistent definitions and capture both successes and failures. Publishing negative or inconclusive cases prevents bias and helps refine matching criteria and delivery protocols. Registries that allow pooled analyses across centres will increase the precision of effect estimates and safety signals.

What NHS services need to be built

Moving from occasional compassionate use to a commissioned service requires investment across the pathway. Laboratories need validated assays for phage susceptibility testing and secure systems for isolate tracking. Pharmacy aseptic units need procedures for receipt, preparation, labelling and controlled dispatch of living medicines. Clinical teams require clear referral criteria, matching workflows and escalation plans if initial responses are partial.

Information governance must support timely exchange between laboratories and clinical teams, with standardised reports that link isolate identity to phage activity. Training is essential. Infectious disease specialists, surgeons, pharmacists and nurses need a shared vocabulary and standard operating procedures so that courses are delivered safely and consistently.

Commissioners will ask for outcome measures and budget impact. That means defining patient groups where biological plausibility and prior evidence are strongest, setting endpoints that capture device retention, length of stay and antimicrobial days, and designing audits that inform procurement. Contracts with suppliers should specify potency ranges, delivery timelines and responsibilities when reformulation is required.

A critical view of expectations

Phages are not a universal replacement for antibiotics. Their strengths align with specific scenarios. They make sense when culture and susceptibility are available, when source control is planned or underway, and when diffusion barriers or biofilms limit antibiotic efficacy. They are less valuable when the pathogen is unknown, when deep tissue penetration is required from the outset, or when immune clearance is likely to deplete phages before activity starts.

Overpromising will harm adoption. The message for clinical teams and policymakers is straightforward. Use phages where matching is robust and delivery is feasible. Invest in manufacturing quality and trial designs that generate credible evidence. Build networks that spread expertise and reduce postcode variation. Keep antibiotics in the plan and combine modalities intelligently.

Conclusion: a new tool for a complex problem

Phage therapy has re-entered mainstream discussion because the AMR crisis demands solutions that match bacterial defences with equal sophistication. The science now supports targeted, biofilm-active, self-limiting agents that can be combined with surgery and antibiotics to salvage cases that would otherwise fail. The regulatory and operational hurdles are real and will determine whether access expands beyond small numbers of bespoke treatments.

For the NHS, the path forward is practical. Develop shared libraries and susceptibility testing capacity. Strengthen MHRA-aligned governance for specials and compassionate use while larger authorisation frameworks mature. Support GMP scale manufacturing and analytics to ensure consistent quality and timely release. Train pharmacists and clinical teams to handle sourcing, compounding, labelling and monitoring for a living medicine. If these building blocks are assembled, bacteriophage therapy can move from last resort to a defined option within multidisciplinary care for resistant infections.

Phages should be judged as a targeted addition to the antimicrobial toolkit rather than a wholesale replacement. Their value lies in cases where conventional medicine has run out of room. Their future depends on regulatory harmonisation, industrial-scale manufacturing and disciplined clinical use. If those conditions are met, a century-old concept can help modern services hold the line against antimicrobial resistance.